Family Member![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I don't have the time to get him back to the condition he deserves to be in

HD video, 6min with soundtrack 'Max is a good lad' by Sophie Mallett, 2019

He's been a lovely family friend and we'll be genuinely sad to see him go

Silicone rubber, hydro dipped polyurethane resin, plaster polymer, cable, 2019

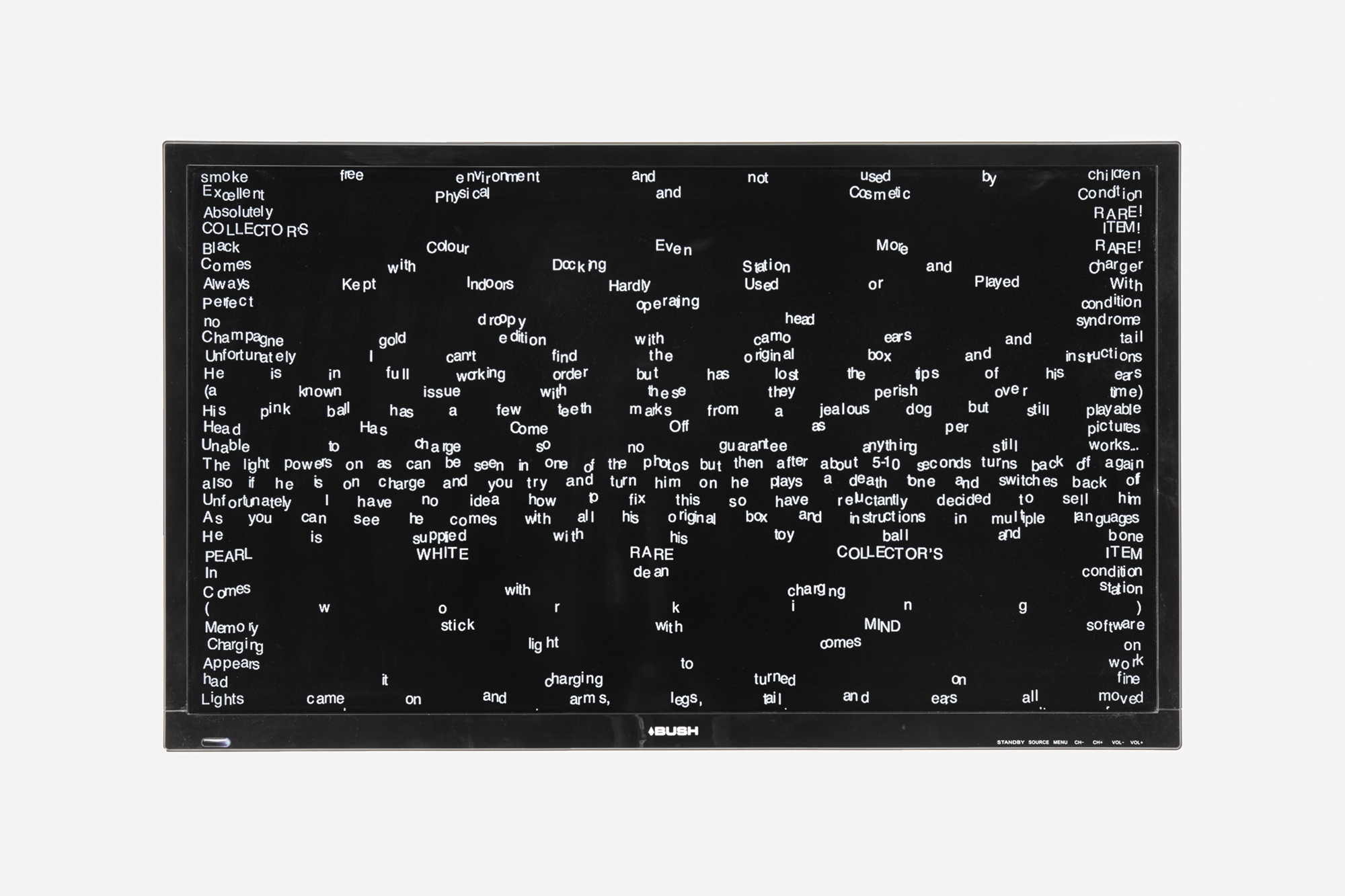

Excellent condition, smoke free environment and not used by children

Silicone rubber, hydro dipped polyurethane resin, 2019I had a little play with him today and absolutely fell in love all over again

Pewter (in some cases with additional epoxy putty features) 2019In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Tamagotchi was placed into our hands, psyches, and pockets. It happened just as we reached the age when playgrounds no longer interested us but the iPhone didn’t yet exist. As the newest commodity fad it quickly became central to friendship circles, and lunchtime myth- making, enabling us to access entertainment as an escape from classroom reality. In reflection, theTama (as I remember it referred to) was an excellent companion for us lonely kids that needed attention, feedback, and responses that we weren’t receiving in a real life setting. Perhaps Tama was an antidote, or an omen, to the logic of late capitalism permeating everything—even our intimate relationships.

The Tamagotchi was the world’s first virtual pet, a simple 3-buttoned portable egg-shaped device that attached to a key ring. Not that any eight year old necessarily had keys for a house on which to attach their pet, but the indication symbolised ownership of a space and of something other than ourselves. Tamagotchi enchanted us. We shared strategies of how to best look after the strange low-res amoebic cyborg creature. We minded each other’s pet as temporary relief from the duties and responsibilities it demanded. We gave our pets names. Though simulated, we related to it as if it was a real living organism and created our own community around it.

The interactive creature needed to be fed, played with, given medicine as well as have their poo cleaned up. Using a human-like vocabulary, it mimicked the activity and corporeal upkeep of any biological being. It beeped sporadically when it wanted your attention, and at times, without reason, refused your care just like any other living dependant. Indoctrinated as a player, you assumed the role as caregiver and in turn were required to be a vigilant. Even though the labours were menial, your input grew your Tama and its image as well as its personality, health, and lifespan. Tama didn’t resemble any particular natural organism in its form; part animal, part human, part machine, part plant, and part blob. Tamagotchi’s identity was based on its social and emotional relationship with you, and your role was to never kill your Tama. I’m pretty sure many egg-shaped objects exist in drawers somewhere.

I cannot help but reflect on the conditions of its wide appeal and popularity. Tamagotchi was born of an increasingly globalised world, an age defined by increased movement of people and goods and the proliferation of image-based media, the last years of a pre-internet age. Like a smartphone now, Tamagotchi was a prosthesis attached to us without us needing to be located to a home or a place. Most pets in our real lives are unable to do this, as they need specific environmental conditions or territories to relate to. It was grounding to bond with a synthetic life form existing just as much in the virtual and the real as in artifice and nature. Tamagotchi’s identity is a fluctuating assemblage—a scattering of shifting subjectivities (much like we as humans are now).

Recently, I humoured myself into buying one. Like many in our mid-thirties I am not having children and would like a dog for company. A Tama made an appealing prospect, as it was low cost, gave me no allergies, could stay with me and would fit in a small flat. I was embarrassed when it beeped in a meeting with someone I had never met before, and upon whom I was attempting to make a good impression. I fessed up and they too were nostalgic and quite disbelieving that they still existed. One or two friends have also said that they wanted to dig out their old companions and reboot them.

Written by Sarah Rose

Photos courtesy of Corey Bartle-Sanderson and Lily Brooke.